Rebuilding Windows Live Messenger, Part 2: Messenger on macOS

Just to take a breath between Assembly and graphics, I installed Mojave on an old Mac Mini and spun Microsoft Messenger, which is the equivalent of Windows Live Messenger for macOS, as removing Windows from the equation makes things way easier. The objective today is to fool it enough to make it think it is talking with the now long gone Microsoft servers.

The first step to make this way easier is to enable logging for

troubleshooting, which happily dumps really interesting stuff into

~/Library/Logs/Microsoft-Messenger.log.

The Login Dance

Once an email and password is provided, the client immediately opens a raw TCP

connection to messenger.hotmail.com, port 1863. This seems to be the server

that speaks the MSNP protocol, given the very first message from the client:

VER 1 MSNP16 MSNP15 MSNP14 MSNP13 CVR0

The protocol is fairly simple: text-based, each message ending in CR-LF. It has the following format:

VER 1 MSNP16 MSNP15 MSNP14 MSNP13 CVR0

━┳━ ┳ ━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

│ │ │

│ │ └──▶ Payload

│ └──▶ Message ID

└──▶ Operation

The message begins with an operation code, followed by the message ID, and a payload. The server always responds with the same message ID, and a corresponding operation code and payload.

The VER operation is a handshake between the client and server. The client

announces the protocols it supports, and the server answers with one of the

protocols it supports. So the fake server can just pick the highest one and be

done with it.

I suppose CVR stands for two different things during the flow. When sent by

the client, it may be a Client Version Report, meaning “I use the base CVR

capability schema, revision zero”. For the server reply, CVR may be a

Capability Vector Revision, but I can’t confirm that. Echoing the CVR0 back

to the client is enough to make it happy.

This leads to the following response from the server:

VER 1 MSNP16 CVR0

Once the version is agreed between parties, the communication continues with the client sending:

CVR 2 0x0409 mac 10.14.6 i386 macmsgs 8.0.1 macmsgs [email protected]

This is the Client Version Report, containing the following fields:

-

0x0409: Microsoft’s LCID (Locale ID) in Hex.0x0409is simplyen-US; Italian, for instance would be0x0410. -

mac: Platform/OS family. -

10.14.6: OS version string. -

i386: Architecture. This seems to be hardcoded in the binary. -

macmsgs: Client product identifier. Just identifies as Microsoft Messenger for Mac. -

8.0.1: The client version. -

macmsgs: Again. Not sure why. -

[email protected]: User identity. That’s me!

Even though the client waits for a response, what the server returns doesn’t seem to be used at all. My theory is that this may be just telemetry, or a mechanism for Microsoft to block old clients or architectures.

For now the fake server is replying with CVR 2 1 2 3 4 5, and Messenger is

happy. After getting the reply, the client then starts the real authentication

flow:

USR 3 TWN I [email protected]

From observation, USR is the User Authentication OP. Decoding it:

-

TWN: I assume this means Ticket With Nexus, considering what happens later. -

I: Seems to be the authentication phase the client is currently at.Imay indicate Initiate? Initial? -

[email protected]: That me, again! This just includes whatever the user inputs in the login “Email” field.

The server then replies with some metadata that’s opaquely handled by the client

and appended to an HTTP Authorization header. So the server can reply with

literally anything:

USR 3 TWN S fake=1

Then things shifts a little:

The Passport Backend

While still connected to the TCP server, the client opens a separate connection entirely – a concurrent, out-of-band flow to the defunct Passport.net server. Not without caveats, though.

All communication with Passport.net uses TLS – Actually, not TLS. SSL. – A really old one: SSLv2 Hello, TLS 1.0. And the best part is that OpenSSL dropped that a while ago. What I need now is a CA Root installed on Mojave, and a TLS terminator so I can continue observing traffic.

So I got a certificate for nexus.passport.com, and wrote a little TLS shim

in C to route TLS traffic from Mojave to my alpine box running the fake servers.

Just a matter of compiling OpenSSL 1.0.2u, accepting the connection with the

right certificate, and proxying the raw TCP data. OpenSSL was linked statically

with the final binary, so we don’t break the whole OS.

The first request is a GET to /rdr/pprdr.asp. With some guesswork we can

assume rdr stands for Redirect or Redirector, and pprdr may stand for

Passport Redirect(or) – naming those things don’t really matter, but it’s nice

to give names to those pesky abbreviations Microsoft uses.

The response has no body, but the client expects an HTTP header named

PassportURLs with a few fields:

-

DARealm: The realm name. Not used by the client, but it requires it to be present. -

DALogin: The realm host and login path. Microsoft seemed to usenexus.passport.com/login2.srf. The lack of schema is intentional, the client will use HTTPS. If you are wondering, DA stands for Domain Authentication. -

Properties: Not used by the client, but it requires it to be present.

Those pairs get concatenated as K=V separated by commas.

Then, the actual login magic happens. The client POSTs to DALogin without a

body, but with an interesting header:

Authorization: Passport1.4 fake=1,OrgVerb=GET,OrgURL=http%3A%2F%2Fmessenger.msn.com,sign-in=hey%40vito.io,pwd=asdf

Breaking it down:

-

Passport1.4: The authentication mechanism version. Hardcoded. -

fake=1, the opaque value provided by the TCP server on theSphase of theTWNoperation. Everything connects! -

OrgVerb=GET: I honestly have no idea what that’s supposed to be. Maybe something for federation, or to allow Messenger servers outside Microsoft? -

OrgURL=http://messenger.msn.com: Same asOrgVerb. -

[email protected]: The identity of the user being authenticated -

pwd=asdf: The password provided by the user on the login window.

The response can again have an empty body, but the client expects a specific header to be present:

Authentication-Info: Passport1.4 da-status=success,from-PP='a=HENLO'

Breaking it down:

-

da-status: The status returned from the Domain Authentication. Here we are indicating the authentication was successful. -

from-PP='a=HENLO': Assuming this as From Passport. The value is opaque to the client, it just returns this to the TCP server.

This is the last interaction with Passport – for now! The dance continues with the TCP server again, where the client sends the following message:

Back to TCP

USR 4 TWN S a=HENLO 235411cb78234a468feb6f1bccca43fd

Same OP, different message ID – as it’s a new message, – and the value returned from passport is handled opaquely and just returned to the TCP server. The final hex is 32 characters – MD5-length – but I haven’t confirmed what it represents. Correlation token, telemetry, session nonce; take your pick.

With this, the TCP server can just FINALLY complete the authentication flow by replying with:

USR 4 OK [email protected] 1 0

-

OK: Authentication passed. Hooray. -

[email protected]: The user’s identity -

1: Authentication flags.1seems to be enough to keep the client happy. -

0: Capability flags. Just echoing from CVR.

Should we expect something else over TCP now? Absolutely not. The plot thickens:

Microsoft SOAP Services

Microsoft loves SOAP for reasons one can’t even reason about. As I’m just trying to boot the app, and not actively use it, the idea is to just provide the minimal amount of stuff to make it get to the main window post-login.

Looking at how the client uses those endpoints, I can again just provide what

it deems required. One interesting thing to notice, however, is that for each

SOAP endpoint, the client seems to perform authentication once again against the

Passport service, and relays whatever the authentication endpoints provides in

response to a TicketToken field.

SOAP goes – at least initially – to one endpoint:

byrdr.omega.contacts.msn.com receives a POST request for

/abservice/SharingService.asmx, with an HTTP header

SOAPAction: http://www.msn.com/webservices/AddressBook/FindMembership,

followed by another POST, this time to /abservice/abservice.asmx,

with the same header, but this time containing the value

http://www.msn.com/webservices/AddressBook/ABFindAll.

On those, FindMembership seems to be responsible to indicate the membership

graph. The MSN Address Book service (aka abservice) has several logical lists,

where each one corresponds to a different kind of “membership” in a materialised

view for the current user. Those lists are:

-

FL: The Forward List, representing one’s contacts (people one added) -

AL: The Allow List, representing who can see one’s presense status. -

BL: The Block List, containing blocked contacts. -

RL: The Reverse List, containing who added the user (reverse ofFL). -

PL: The Pending List, containing pending invitations.

FindMembership provides the AL, BL, and RL lists, while ABFindAll

returns what’s enough for the client to rebuild the FL list.

ABFindAll is a different story; it returns the full contact records for the

authenticated user. Each record contains several fields, including:

-

contactId: a GUID representing the contact. -

contactType: the contact’s type.Regularis the only value that’s of my interest right now. -

passportName: the user’s Passport name. Basically their email. -

displayNameandquickName: the user’s display name. Not sure why it is sent twice.

The object may contain lots of other fields, but those are the most relevant to achieve our objective.

Once those SOAPs are returned, the client resumes communication with the TCP server:

The Final Dance

The next operation requested by the client is a new kind we haven’t seen yet: a two-part operation. This is what is sent:

ADL 5 245\r\n

<ml l="1"><d n="local"><c n="away" l="3" t="1" /><c n="brb" l="3" t="1" /><c n="busy" l="3" t="1" /><c n="hidden" l="3" t="1" /><c n="idle" l="3" t="1" /><c n="lunch" l="3" t="1" /><c n="online" l="3" t="1" /><c n="phone" l="3" t="1" /></d></ml>

This will need some explanation. Through the previous SOAP, I’m setting a few users to have each one showing a different status. Here are the users:

GUID Passport

------------------------------------ -------------

11111111-1111-1111-1111-111111111111 online@local

22222222-2222-2222-2222-222222222222 busy@local

33333333-3333-3333-3333-333333333333 idle@local

44444444-4444-4444-4444-444444444444 away@local

55555555-5555-5555-5555-555555555555 brb@local

66666666-6666-6666-6666-666666666666 lunch@local

77777777-7777-7777-7777-777777777777 phone@local

88888888-8888-8888-8888-888888888888 hidden@local

ADL is the Address List command. The payload 245 indicates how many bytes

follow after the terminator (\r\n), comprising a second payload, that’s

formatted below:

<ml l="1">

<d n="local">

<c n="away" l="3" t="1" />

<c n="brb" l="3" t="1" />

<c n="busy" l="3" t="1" />

<c n="hidden" l="3" t="1" />

<c n="idle" l="3" t="1" />

<c n="lunch" l="3" t="1" />

<c n="online" l="3" t="1" />

<c n="phone" l="3" t="1" />

</d>

</ml>

The XML contains a single ml (Membership List) element with an l attribute

with value 1, indicating this is the first list exchanged through the ADL OP.

Each sub-list is split by domain, and since all my users are @local, we get

a single d (Domain) element, with the n attribute set to local. Inside

we have each user as a c element, their name in the n attribute, l (List)

set to 3, which is a bitmask indicating that the contact is both on FL and AL

lists and t (Type) set to 1, indicating a Passport-type identity.

The bitmask values are:

-

1= Forward List (FL) – contacts the user added -

2= Allow List (AL) – contacts allowed to see the user’s status -

4= Block List (BL) -

8= Reverse List (RL) -

16= Pending List (PL)

For now we just acknowledge the message, so it can continue with its process:

ADL 5 OK\r\n

The next OP we get from the client is PRP:

PRP 6 MFN [email protected]

PRP stands for Profile Property. The client is requesting a property to be

set: MFN, also known as My Friendly Name. Again, we just need to acknowledge

it, but this time with an ACK OP:

ACK 6 PRP\r\n

The client continues with:

BLP 7 AL

BLP is the Blocking Policy. It controls the default privacy rule for people

not explicitly on AL and BL. The last token we get is the policy to be

applied, which can be one of:

-

AL: Allow by default. Unknown users can see and contact the current user. -

BL: Block by default. Only allowed users can see and contact the current user.

The client is setting the policy to Allow. Ok. We just acknowledge it again:

ACK 7 BLP\r\n

Next up: Status update. The client sends:

CHG 8 NLN 1085276192:131088

CHG requests a status update, NLN indicates Online, and is followed by

an optional capability bitmask (two numbers, colon-separated). For now I’ll

ignore those, but they will be important in the future, depending on how this

progresses.

For this one we will echo everything back to the client:

CHG 8 NLN 1085276192:131088\r\n

But this change is also an important trigger for the TCP server. From this point

onwards, the client accepts the Initial Status List, (ILN) which assigns

statuses and Display Names for each one of its contacts, followed by an UBX

OP that provides extra information regarding their profiles, such as a Personal

Status Message, and Media Status.

Here we reuse the Message ID from CHG to send one ILN for each contact,

along with an UBX. Notice, however, that UBX takes no Message ID. From

the previous contact list, I’ll also assign a random UUID for their PSMs:

ILN 8 NLN online@local 1 Online%20User 1085276192 %3Cmsnobj%2F%3E\r\n

UBX online@local 1 89\r\n

<Data><PSM>0b48cf1c-b9a5-4793-b8d4-a8ddd6b13c6c</PSM><CurrentMedia></CurrentMedia></Data>

ILN 8 BSY busy@local 1 Busy%20User 1085276192 %3Cmsnobj%2F%3E\r\n

UBX busy@local 1 89\r\n

<Data><PSM>72b6dca4-811b-4c6a-8b2a-c87cfa6e3299</PSM><CurrentMedia></CurrentMedia></Data>

ILN 8 IDL idle@local 1 Idle%20User 1085276192 %3Cmsnobj%2F%3E\r\n

UBX idle@local 1 89\r\n

<Data><PSM>88360ef7-5152-4ada-8bc8-e0343736e830</PSM><CurrentMedia></CurrentMedia></Data>

ILN 8 AWY away@local 1 Away%20User 1085276192 %3Cmsnobj%2F%3E\r\n

UBX away@local 1 89\r\n

<Data><PSM>d430617a-17bf-4437-a8f2-54aa4d33444e</PSM><CurrentMedia></CurrentMedia></Data>

ILN 8 BRB brb@local 1 Brb%20User 1085276192 %3Cmsnobj%2F%3E\r\n

UBX brb@local 1 89\r\n

<Data><PSM>ecd12daf-0c11-445f-b1ae-4751a509c25c</PSM><CurrentMedia></CurrentMedia></Data>

ILN 8 LUN lunch@local 1 Lunch%20User 1085276192 %3Cmsnobj%2F%3E\r\n

UBX lunch@local 1 89\r\n

<Data><PSM>9bd609bc-d2f8-4e1a-be72-06804bf73183</PSM><CurrentMedia></CurrentMedia></Data>

ILN 8 PHN phone@local 1 Phone%20User 1085276192 %3Cmsnobj%2F%3E\r\n

UBX phone@local 1 89\r\n

<Data><PSM>b1482981-ad81-4a2a-872f-ba3331c6bb91</PSM><CurrentMedia></CurrentMedia></Data>

The ILN command has the following parameters after the Message ID:

- The status (

NLN,BSY,IDL,AWY,BRB,LUN,PHN) - Their email address

- Their Network ID (

1= Passport/Windows Live) - Their display name, URL Encoded

- Their capabilities flag. Here I’m sending the same caps the client provided to the server, except that it only takes the first portion (before the colon).

- A

msnobjpayload. Here it is empty, and has no significance to my objective.

UBX has the same format as UUX (see below).

As a side note, the required

msnobjportion was what took most of the time during this session. Without it the client just refused to assigned statuses and failed silently. Codepaths leading to this portion were also quite complicated, so getting to the point “oh, that’s what’s missing” took a while.

Then, more state is sent by the client:

UUX 9 53

<Data><PSM></PSM><CurrentMedia></CurrentMedia></Data>

UUX (User eXtended data) is a set of metadata announced by the client. Here

it’s setting the PSM (Personal Status Message), and the CurrentMedia to

empty values. Again, we just acknowledge it:

ACK 9 UUX\r\n

Following, we get two extra UUX messages:

UUX 10 75\r\n

<EndpointData><Capabilities>1085276192:131088</Capabilities></EndpointData>

and

UUX 11 92\r\n

<PrivateEndpointData><EpName>Rhodes</EpName><ClientType>1</ClientType></PrivateEndpointData>

The first one contains the same capability set we got during the CHG OP. The

second is part of the “multi-endpoint” implementation that was being rolled,

allowing users to sign in in multiple places at the same time. It contains

the endpoint name EpName, that’s carrying the name of the computer running

Messenger (Rhodes), and a client type. We can assume 1 represents a Desktop.

Then, the client continues asking for a service URL using the URL OP:

URL 12 MOBILE

There it is asking specifically for the Mobile Messaging / SMS Service MSN used to support. For now, let’s just route it to our server:

URL 12 MOBILE http://10.0.10.126:8080/\r\n

And continues with further URL ops:

URL 13 PROFILE 0x0409

URL 14 CHGMOB

PROFILE is requesting the profile webpage/service URL for a LCID in hex,

again, 0x0409 is en-US. CHGMOB is the Change Mobile settings URL,

part of the MOBILE capability. For both we will reply the same URL as

MOBILE, as the client wouldn’t care anyway.

Followed by:

UUN 15 [email protected] 8 9

ignore me

I think UUN is User Update/Notification the value 8 is unknown, and 9

represents the amount of bytes following. For some reason, the client is sending

ignore me. Weird. After some Trial-and-Error, the client is happy with a

simple ACK:

ACK 15 UUN\r\n

And finally, the client rests sending periodic PNG (Ping) OPs:

PNG 16\r\n

QNG 60\r\n

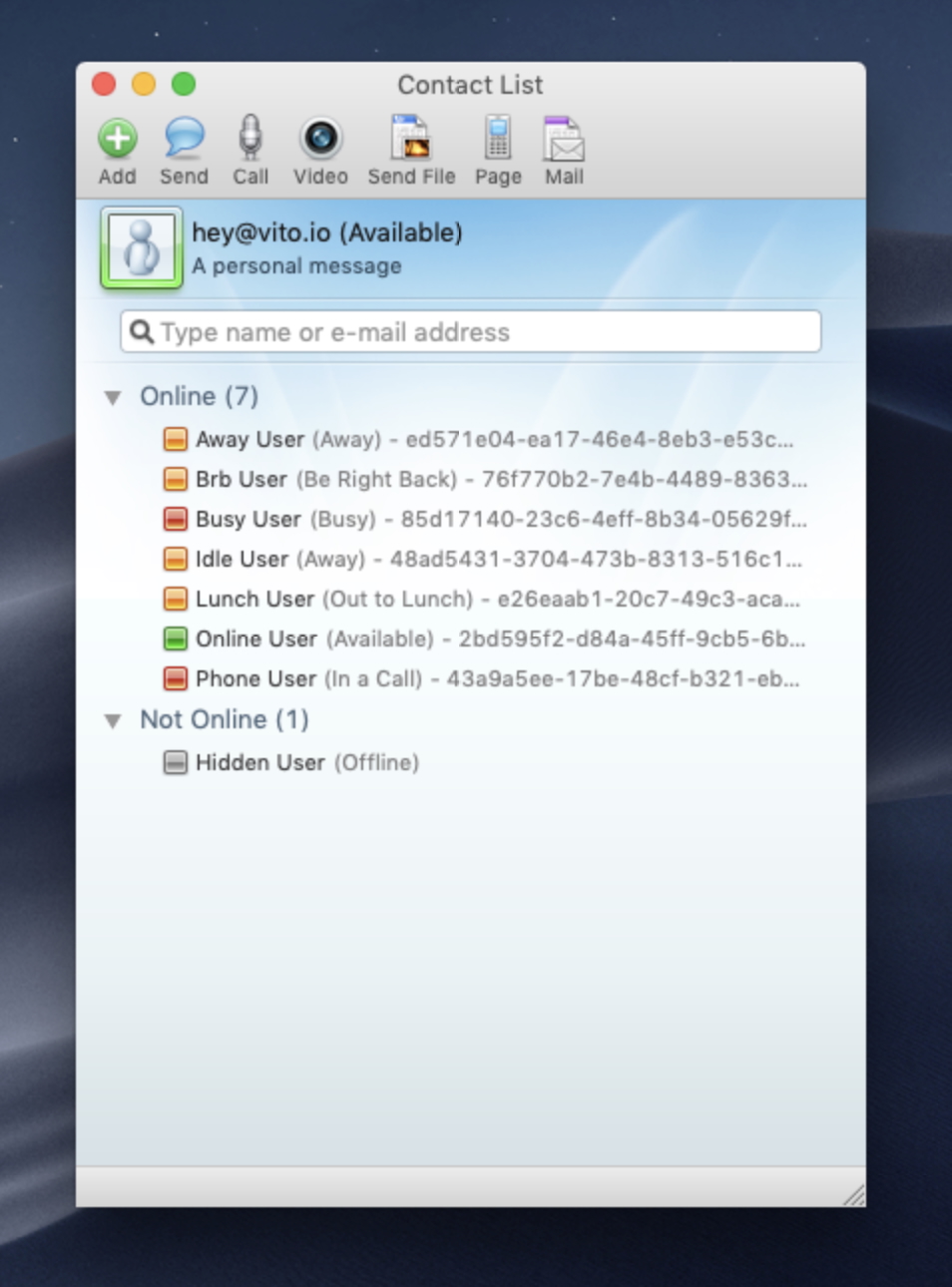

The result is nothing less than satisfying.

And there it is. Eight contacts, eight statuses, no Microsoft infrastructure involved. A fake TCP server, a TLS shim, a handful of SOAP responses, and a lot of trial and error – enough to convince a 2008 Mac app it’s talking to servers that haven’t existed for over a decade.

That was just a little detour try to relax from the amount of Assembly and C/C++ on Windows. Did it work? No, I had to disassemble the macOS binary, but at least that is known territory.

Later on I will continue on the main project.